Architecture

BUILDING THE AMPHITHEATRE

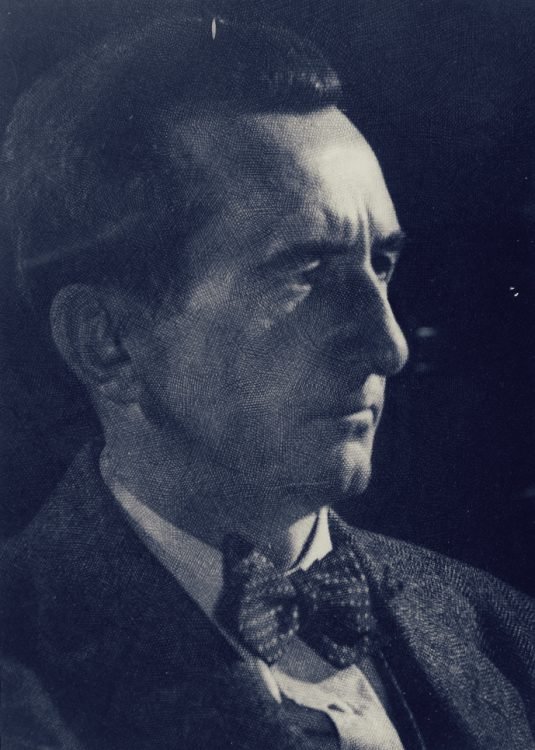

As one of Colorado’s most spectacular settings, Red Rocks attracted the state’s most celebrated piece of architecture. Its amphitheatre is the master work of Colorado’s most highly regarded architect, Burnham Hoyt.

Hoyt realized from the beginning that the challenge was “to do a minimum of architecture; to preserve in full where possible the great assets of the site: the view and the extraordinary acoustic properties.” Showing reverence for this sacred site, Hoyt also realized that the most “important preliminary work to be done” was “to convince nature lovers” that constructing an amphitheatre would not mar the site’s natural beauty.

In his report on the project, Hoyt elaborated:

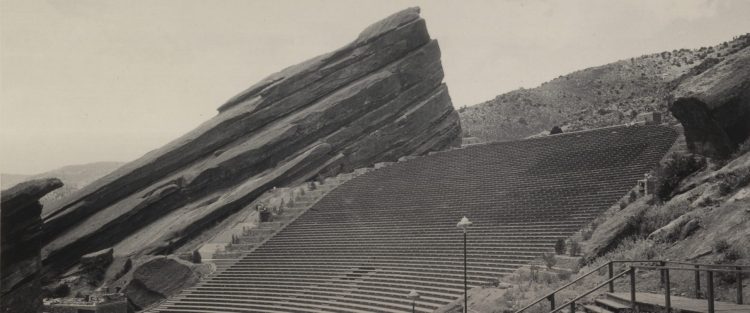

The Park of the Red Rocks is filled with huge red sandstone monoliths generally tilted at an angle of 30 degrees toward the west. The rocks are intensely red in color and of fantastic shapes. Between two of the largest, Creation Rock on the north and 300 feet high and Ship Rock on the south 200 feet high, lies an open space 320 feet wide and 480 feet long dropping 100 feet in altitude to a smaller eastern rock known as Stage Rock. . . Aside from the spectacular scenery, its acoustic properties are amazing – a whisper carries to the top of the seating area. Music was particularly successful and the wish of those familiar with the weird beauty of the spot had always been for a fitting theater here.

The Architect

Born in Denver in 1887, Burnham was the son of a carriage designer, Wallace Hoyt. Growing up in North Denver, Bernie attended the Boulevard School and North High then began working with the Denver architectural firm of Kidder and Weiger. At the urging of his older brother, Merrill, an architect, Burnham pursued formal architectural training at the Beaux Arts School of Design in New York City. After graduating, he worked with the prominent New York firm of George B. Post and Bertram Goodhue. In New York he worked on such projects as St. Bartholomew’s and Riverside Churches and taught architecture at New York University. During World War I, Burnham served as an army camouflage designer in France.

In 1919, Hoyt returned to Denver to form a partnership with his brother Merrill. Hoyt & Hoyt designed in historical revival styles, and created some of Colorado’s first notable modern work, such as the Boettcher School for Crippled Children and an addition to the Albany Hotel. The Hoyts designed many stylish Colorado residences ranging from a medieval Scottish castle on the Cherokee Ranch in Sedalia to the Art Deco Sullivan House at 545 Circle Drive in Denver. Burnham did important additions to the Broadmoor Hotel and Palmer High School in Colorado Springs, as well as work on the Central City Opera House.

Forced into retirement by Parkinson’s disease, Hoyt completed his design for the 1955 Denver Public Library before closing his office and turning his remaining work over to the firm of Fisher and Fisher. Following Hoyt’s death at his home April 6, 1960, his widow Mildred donated his papers to the Western History Department of the Denver Public Library. That collection includes 74 drawings for the Red Rocks Amphitheatre done between 1935 and 1940.

The Amphitheatre

More than 125 schematic and construction drawings were produced between 1935 and 1941 as construction progressed. Working under Hoyt’s supervision, Stanley Morse, who did much of the day-to-day work at Red Rocks, would visit the site every morning and then got to his office to do drawings, rather than do drawing in his office and make the site and structure conform to an abstract design.

Morse produce detailed drawings for the preliminary grading and sight lines and for the stage and amphitheatre, including such details as toilets, signage, dressing rooms, the movie projection booth and even water, sewage and drainage lines. These drawings focused on “redwood bench detail,” “handrail detail,” and the north and south “planters” for the juniper trees. These native evergreens, which adorn the surrounding hillsides, seem to wander naturally into the amphitheatre.

Several major changes evolved in the building process. Only after excavating the base of Stage Rock did Morse chalk out a level on the rock for a huge stage 150 feet long and 60 feet deep. Bulges in the rock became features in the dressing rooms. Likewise, Morse and Hoyt changed the seating arrangement when protruding ledges at the base of Creation Rock disrupted the original symmetrical plan. They moved the northern stairway to the south, thus eliminating some of the seating. This created an asymmetrical auditorium with fewer seats on the north side than on the south.

George Cranmer boasted of the venue’s technological innovations. He told the press in April 25, 1939 that “at no cost to the city” Mountain States Telephone and Telegraph Company had agreed to rig the amphitheatre with “a $10,000 wiring system so that future musical programs could be broadcast to the world.” Cranmer also announced that the city had installed a reservoir high up on Mount Morrison “served by springs gushing out of the mountain to supply drinking water to thousands and operate the plumbing system under the stage and ramps.”

“There will be nothing quite as wonderful in the world,” Cranmer crowed. He added that the theater would be edged with juniper trees and mountain flowers and shrubs planted around the rocks and irrigated by the Mt. Morrison reservoir. Like any proud father, Cranmer closely monitored the theater’s development. His daughter, Sarah Cranmer McLaughlin, recalled that her father loved to take the family on Sunday drives up to Red Rocks to watch the progress. Having accompanied her father when he saw the prototype theater in Sicily, Sarah appreciated her father’s weakness for “romantic opportunities.”

Improvements over the Years

Stanley E. Morse, who had been Hoyt’s main assistant on the amphitheatre, addressed wind, lighting and sound problems by designing two-story lighting towers and wind walls for the north and south ends of the stage. These structures also provided for expansion of the dressing rooms under the stage. The original orchestra pit was covered over and converted to storage. The stage was replaced and the trap doors removed.

This $175,000 improvement was completed in July, 1959 for the opening of the Red Rocks Music Festival’s production of Puccini’s “Girl of the Golden West” and Denver’s “Rush to The Rockies” Centennial Celebration.

In 1988, the city installed a large metal roof over the stage. During the late 1990s and the early 2000s, Red Rocks enjoyed rejuvenation with a new Visitor Center and refurbishing of the amphitheatre and park.